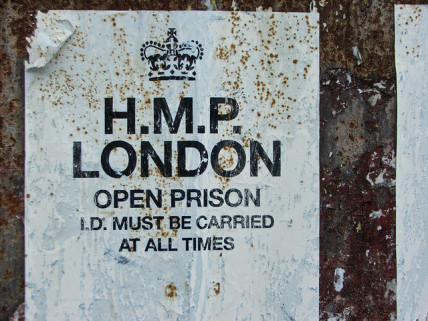

Photograph by Ben Scicluna

The UK government packaged its privatisation of probation services in England and Wales yesterday as ‘the most significant reforms to tackling re-offending and managing offenders in the community for a generation’. A leading campaigner for prison reform peers beneath the packaging.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. I am reminded of this old adage when I consider Justice Secretary Chris Grayling’s plans to allow private firms and charities to supervise people on probation in England and Wales.

Mr Grayling tells us that the number of people who go on to commit more offences after being released from prison is too high. And he is right. But in trying to do something about it, this government is in danger of making the problem worse.

The answers as to why so many people who leave prison quickly return to a life of crime don’t lie with the Probation Service, but with the government’s own sentencing policies. Too many people are being sent to prison to serve short jail terms when community sentences would be more effective. The probation service doesn’t manage these people on release, so it is disingenuous to exploit the high reoffending patterns of people sentenced to short periods in prison to slam the Probation Service. Indeed, it seems the Justice Secretary is going a step further, and privatising probation for a failure that they are not responsible for.

Our prison population has doubled since the early 1990s, leaving jails overcrowded and staff overstretched. It should come as little surprise that they are so poor in helping people turn their backs on crime.

The Probation Service, by comparison, has a stronger record of success than our prisons, with only 34 per cent of people on court orders going on to commit crime again.

Statistics show that people who have served long prison sentences pose a much lower risk of reoffending than those who are released after shorter terms. It is surely no coincidence that these prisoners have benefited from better, more intensive contact with the Probation Service, an organisation with a proven track record for helping people rebuild their lives.

There is no evidence to suggest that the Justice Secretary’s experiment in privatising the Probation Service will deliver any improvements. This is mainly because the Ministry of Justice itself cancelled many of the payment by results pilot projects which had been put in place.

Indeed, our experience of privatisation in crucial security and justice services has proven a dismal failure, with priority given to shareholder profit not public safety. We have seen, for instance, the tragic deaths of children in private prisons, as well as the need for armed forces personnel to step in when G4Sfailed to meet its Olympic security obligations.

Particularly concerning is the fact that private firms will be responsible for deciding if someone they are monitoring has gone from being ‘medium-risk’ to ‘high-risk’. That person would need to be transferred back to the public sector, as what remains of the Probation Service will be tasked with supervising those who are believed to pose the greatest risk.

To the private firms, losing a ‘customer’ to the public sector means losing money – a clear disincentive to reporting someone’s increased risk to the public. Given that the level of risk someone poses changes in about a quarter of cases, this is something that should worry us all. The public may also be kept in the dark about what private providers are required to deliver as contract documents will be commercially sensitive.

There is a disturbing lack of detail in the government’s plans. At most we know that probation will be privatised using a similar system of national commissioning as found in the Work Programme, the success of which has been far from clear. Quite how this national commissioning system, divided into 16 geographical contract areas, will work when we have more than 40 Police and Crime Commissioners across England and Wales remains to be seen.

The good news in Mr Grayling’s announcement is the idea of expanded rehabilitation services for those leaving prison after less than a year, but again questions remain. It is clear that the Ministry of Justice lacks the money to deliver any real improvements, so how will this extra provision be paid for?

If the Justice Secretary is serious about saving taxpayers’ money, cutting reoffending and improving public safety, he should look to cut back the number of people going to prison for less than six months, often for non-violent offences. These people should be on community sentences, which are far cheaper and have proven more effective.

The government must also remember that the real solutions to crime lie outside of the criminal justice system. Probation can support people in changing their lives but ultimately it is mainstream public services such as health, employment, education and housing that will have the greatest impact on tackling the underlying causes of crime.

Written by Frances Crook