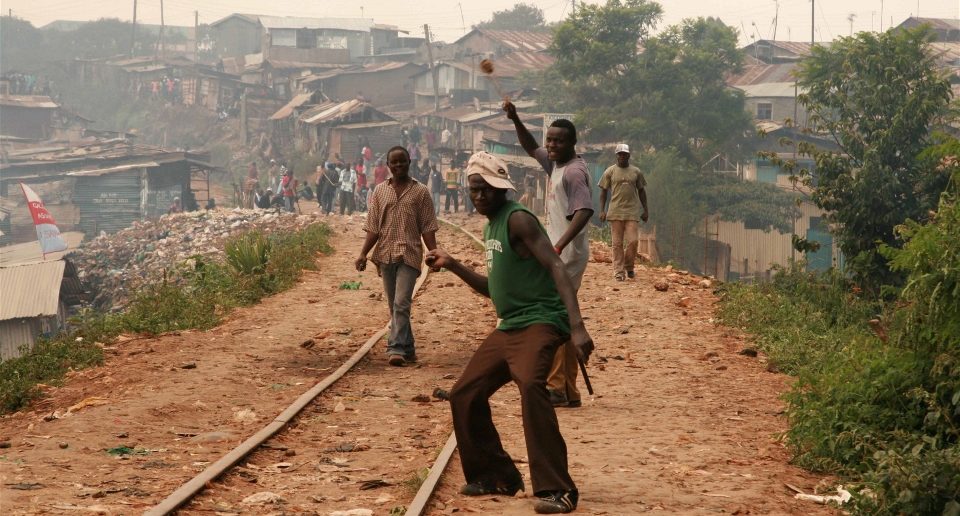

Rowdy youth throw stones in Kibera slums, Nairobi; Kenya. Photograph by Julius Mwelu/IRIN

In slums where killings, rape, kidnappings and other criminal violence are commonplace, say researchers, lives and livelihoods are hampered by a force that is tough to measure: Fear.

“We talk about homicide rates and deaths. Fear is a huge part of the protection mandate, and we don’t measure it well,” said Ronak Patel, director of the urbanization and crises programme at the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative. He said surveys in recent years in slums in the Kenyan capital Nairobi – in a “non-crisis” peacetime setting – showed that 34 percent of people altered their daily activities for fear of violence and a quarter felt afraid in their own homes.

“This doesn’t get measured like mortality rates or rape incidence, but it has a huge impact that the humanitarian community needs to address.” For example this fear affects a woman’s ability to access a market, a prospective workplace or health care, he said.

Carlos Vilalta, professor and researcher at the Center for Economic Research and Education in Mexico City, at a recent conference presented preliminary findings from research under way in Mexico.

Based on government survey data, he estimates that in 2010 it cost a family driven from home by fear of gang violence about US$611 to relocate, where the average monthly income was about $800. Very few studies into the fear of crime exist: it is an area that needs more attention, Vilalta said.

“Governments and particularly the police are obviously working very hard in fighting crime. However they seem to forget that fear of crime is also an issue for civil society and a matter of criminal policy.”

He said the premise that reducing crime will automatically reduce the sense of insecurity is false: “Mexico today has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s and, ironically, fear of crime is much higher.”

The European Commission’s humanitarian aid department, ECHO, says that in Central America, fear of organized violence is a constant.

“A frequent scenario is that people first escape inside the country, trying to seek refuge with family or friends, but are then localized by their aggressors and decide to leave the country,” ECHO said in its 2013 humanitarian implementation plan for the region.

A recent report (Spanish) by the Costa Rica-based International Centre for the Human Rights of Migrants (CIDEHUM ) confirmed that organized crime is driving the displacement of populations in Central America.

Overlooked

The UN Refugee Agency, which commissioned the CIDEHUM study, three years ago issued guidance for assessing whether victims of gang violence may be eligible for international protection. For now in Central America the human impact is largely overlooked, UNHCR said.

“While organized crime is being dealt with from a security angle, such as crime prevention and response, little attention has so far been paid to the impact of this phenomenon from a humanitarian and protection perspective,” the agency said in a February 2013 paper.

The 1951 Refugee Convention does, however, recognize the concept of fear: it defines refugees as individuals with a genuine fear of persecution, not people who have necessarily experienced persecution.

Still, Javier Rio Navarro, Médecins Sans Frontières operational adviser in Mexico and Central America, says emigrants from Mexico or Central America are generally regarded as economic migrants.

“This is no longer applicable to all of them. A significant number of them are survival migrants, or displaced, or as they would be called anywhere else in the world – refugees.”