Severed cables. Photograph by Pascal Charest

Anyone familiar with my recent rants on the subject of Internet regulation may have noticed that I have been slightly obsessed with the subject of network centrality. The Internet is supposed to be a distributed architecture, designed to withstand large-scale attacks. The decentralised nature of the Web allows for systems to be taken out, while the whole still will operate by redirecting traffic through the remaining nodes. This makes the Internet resilient to random attacks.

Or so the theory goes.

We are increasingly seeing a shift in the Web’s basic structure, from a decentralised network we are presented with more centralised services which compromise the Internet’s resilience. Syria and Egypt managed to remove their countries entirely from the rest of the world by pulling a few switches (the operation is of course more complicated than that, but for the sake of brevity we will consider it so). This was not supposed to be possible if we had kept with the original intentions of the decentralised, organic and self-organised system.

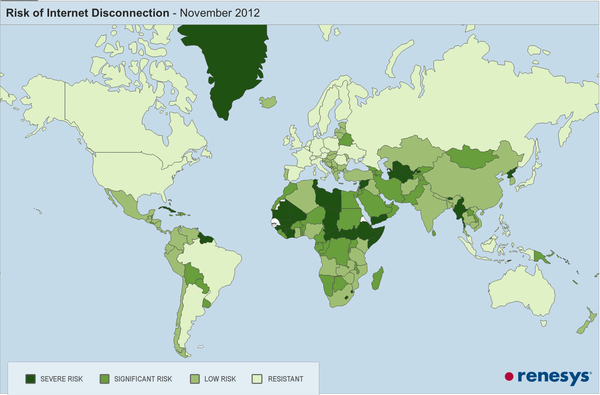

Now a ground-breaking study by employees at Renesys has shed light on just how vulnerable the Web has become at national levels. They have studied a country’s Internet infrastructure by looking both at the physical interconnections that exist throughout the world, and also at the logical network, and have produced a map of the world in which it is clear that some countries are more likely to be disconnected than other precisely because they are more centralised. They used the following parameters:

If you have only 1 or 2 companies at your international frontier, we classify your country as being at severe risk of Internet disconnection. Those 61 countries include places like Syria, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Libya, Ethiopia, Uzbekistan, Myanmar, and Yemen.

If you have fewer than 10 service providers at your international frontier, your country is probably exposed to some significant risk of Internet disconnection. Ten providers also seems to be the threshold below which one finds significant additional risks from infrastructure sharing — there may be a single cable, or a single physical-layer provider who actually owns most of the infrastructure on which the various providers offer their services. In this category, we place 72 countries, including Oman, Benin, Botswana, Rwanda, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uganda, Armenia, and Iran. Disconnection wouldn’t be trivial, but it wouldn’t be all that difficult. Egypt falls into this category as well; it took the Mubarak government several days to hunt down and kill the last connections, but in the end, the blackout succeeded.

If you have at least 10 internationally-connected service providers, but no more than 40, your risk of disconnection is fairly low. Given a determined effort, it’s plausible that the Internet could be shut down over a period of days or weeks, but it would be hard to implement and even harder to maintain that state of blackout. There are 58 countries in this situation, ranging from Bahrain (at the small end) to Mexico (at the largest end). India, Israel, Ecuador, Chile, Vietnam, and (perhaps surprisingly) China are all in this category.

So is Afghanistan, reminding us that sometimes national Internet diversity is the product of regional fragmentation and severe technical challenges. It’s true; the government in Kabul is powerless to turn off the national Internet, because it’s built out of diverse service from various satellite providers, as well as Uzbek, Iranian, and Pakistani terrestrial transit.

Finally, if you have more than 40 providers at your frontier, your country is likely to be extremely resistant to Internet disconnection. There are just too many paths into and out of the country, too many independent providers who would have to be coerced or damaged, to make a rapid countrywide shutdown plausible to execute. A government might significantly impair Internet connectivity by shutting down large providers, but there would still be a deep pool of persistent paths to the global Internet. In this category are the big Internet economies: Canada, the USA, the Netherlands, etc., about 32 countries in all.

The end result is a map that has a worrying amount of green, meaning more chance of disconnection.

Risk of internet disconnection map. Courtesy of Renesys

Research like this must be applauded, and hopefully the issue of centrality will continue to receive more coverage in Internet regulation debates. We seem to be stuck with some non-issues, while sleepwalking into a more centralised and therefore a more controlled Internet.

Written by Andres Guadamuz