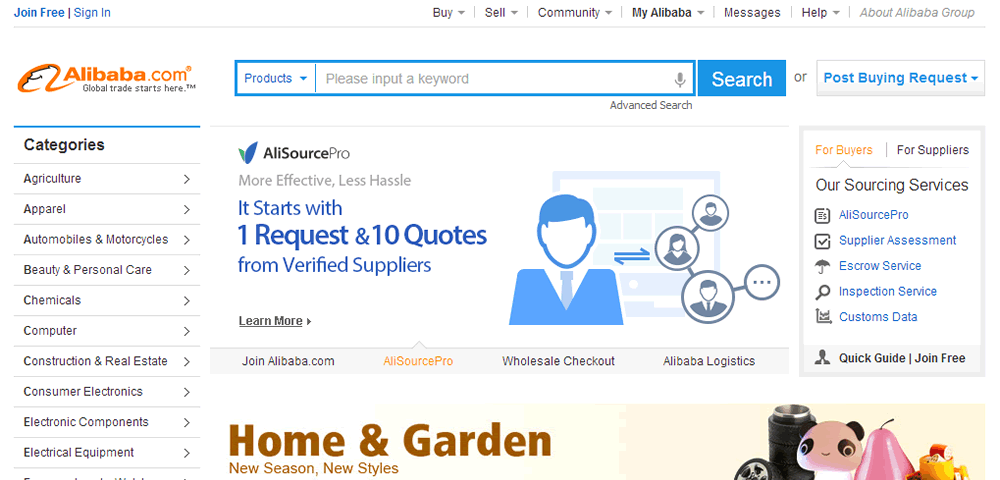

The planned stock market listing of Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba in New York is a landmark deal for several reasons. The listing is anticipated to become the largest in the US since Facebook’s issue in 2012, and there are some key signals it sends about markets and investor sentiment. The company, which operates both an eBay-style marketplace and business-to-business platform Alibaba.com, has been here before. Alibaba.com went public in Hong Kong in November 2007 and its shares remained listed there until the company went private again in September 2012. This time around, Alibaba’s entrepreneur founder Jack Ma has shunned Asia for the bright lights of the Big Apple. The group filed for an initial public offering (IPO) this week, setting in train a process which should see the shares start trading on the New York Stock Exchange or the Nasdaq Global Market in the form of American Depositary Shares. Alibaba Group is not the first successful Chinese online business grabbed by US exchanges. Past examples include Renren (the Facebook of China), Weibo (the Twitter of China), and Baidu (the Google of China), all of which shunned Chinese stock markets and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. The case of Alibaba Group is particularly dramatic for Hong Kong, as the company was initially planning to list there. So the decision offers further evidence of structural problems with Asian IPO markets, and it also signals a fresh appetite for Chinese offerings in the US – or at least among the bankers preparing to sell the stock to investors.

Dot-com Bubble to Social Media Wave

It has been a rocky road for investors in technology stocks. During 1999 and the early months of 2000, it looked as if appetite was insatiable. The frenzy led to unrealistically high valuations; some companies profited by simply adding the .com suffix to their names, even if their business had little to do with the internet. Of course, the bubble eventually burst with a sharp correction in prices and the thirst for internet stocks swiftly dried up. It took a long time before internet firms regained the market’s trust. Google’s successful IPO in 2004 was an important step in this respect. Then came the IPO wave of social media firms. Linkedin, Groupon, and Zynga went public one after the other in 2011. Facebook made its debut in 2012. Twitter followed in 2013. Jiayuan.com and Tudou Holdings joined their Chinese internet peers that went public in the US during this wave. The market is more cautious these days in terms of valuing internet stocks, as can be seen in the less-than-frothy debuts of some of those above. The dotcom bubble and the bear market that followed are still painful memories for US investors. There is less hype about internet stocks and the market reacts efficiently when it feels a valuation is too high, as was the case with Facebook. It means that demand for internet stocks in the US seems less flaky and more likely to be sustained this time around. It is also a relatively good time for Chinese firms to turn to US markets. Accounting scandals concerning Chinese firms that listed shares in the US dented the enthusiasm for new listings in 2011 and 2012. However, these scandals mainly involved Chinese firms that took a shortcut to a US listing by engaging in a reverse merger – sometimes known as a backdoor IPO – and not those that took the normal route. Recently, Chinese issuers are returning to the US IPO market, which suggest a regained confidence in China’s growth story. It all means this should be a comfortable moment for Alibaba to go public in the US.

Keeping control

And that means ChiNext, China’s version of the Nasdaq exchange, and the HKSE are losing yet another major Chinese tech firm to the US exchanges. My colleagues and I have found that ChiNext is not yet ready to attract firms of the calibre of Alibaba Group. For the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, however, Alibaba slipped through their fingers. The US IPOs of Baidu, Renren and Weibo had a common feature that explains much. All of these companies issued class A shares with inferior voting rights compared to the class B shares held by pre-IPO owners. In each case, class A shares are entitled to a single vote, whereas class B ones are entitled to ten votes in the cases of Baidu and Renren and three votes in the case of Weibo. This dual-class share structure is quite common in the US and, crucially, allows insiders to retain control after taking their firms public. Hong Kong Stock Exchange rules do not allow for different classes of shares. And although there are merits in the “one share, one vote” principle, at a practical level, it is one of the key reasons why US exchanges are managing to grab successful Chinese tech businesses. Alibaba’s listing is set to be a landmark whatever the outcome. A positive reception by the market will reinforce a recovery in the US IPO market which has rallied from its dismal state in the heart of the financial crisis. On the other hand, while a negative reaction would dent momentum, the market seems more resilient at present and confidence more established. And of course, a negative reaction might offer some succour to the spurned Asian exchanges if Chinese tech firms think twice before they turn their backs again. By Ufuk Gucbilmez, University of Edinburgh Ufuk Gucbilmez does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.![]()