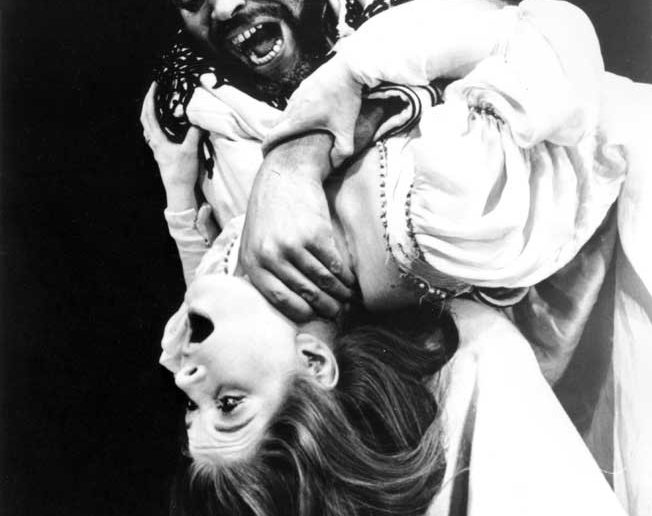

Othello and Desdemona. Photograph courtesy of NYC Parks

Othello Syndrome is a type of delusional jealousy, marked by suspecting a faithful partner of infidelity, with accompanying jealousy, attempts at monitoring and control, and sometimes violence. The problem is named for Shakespeare’s Othello, who murdered his beautiful wife Desdemona because he believed her unfaithful.

I came across Othello Syndrome because of a fascinating article at The Dana Foundation, When a drug leads to suspicions of infidelity. Here we have a mental illness induced as a side-effect in some patients as a result of taking dopamine to help with Parkinson’s disease.

In rare cases the treatment, which attempts to boost dopamine levels, brings on this stubborn delusion, which can transform a previously trusting relationship into a nightmare of suspicion, bitterness, and relentless accusations of infidelity.

The sheer strangeness of Othello syndrome aroused the curiosity of Keith Josephs, a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn.

“I think of Othello syndrome as a delusion —an abnormal thought, sort of like believing in aliens,” said Josephs, winner of the 2009 Judson Daland Prize for outstanding achievement in patient-oriented research. “It’s as though a man decides, ‘My wife is having an affair, and no one is going to talk me out of believing that.’”

As an illustration, Josephs describes a 42-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who started to demand frequent sex from his wife while he was taking pramipexole, a drug that binds to dopamine receptors and mimics the action of dopamine. The man also was taking a combination of carbidopa and levodopa, which work together to boost levels of dopamine in the brain.

Under the influence of these drugs, the man started to accuse his wife of having an affair. He obsessively watched the driveway because he expected to find a car parked there, waiting to pick up his wife so she could go off and have sex. He also lost $3,000 while trying to satisfy a sudden urge to gamble, and came home one day with two new fishing poles even though he already owned five.

The man was a bundle of impulse control disorders, a recognized side-effect of dopamine agonists given to Parkinson’s patients to boost their inadequate levels of dopamine, but Josephs had never seen the drugs produce such an intense belief in a spouse’s infidelity.

“Then I saw a second patient,” he said. “I reviewed the literature and came across Othello syndrome, which described my patient. I thought, if I have seen two patients with this, and everyone else sees two, no one would ever notice the connection, but when you pull 100 patients together into one study, you really have some valuable data.”

Keith Josephs has a 2012 co-authored paper on all those cases he found, Clinical and imaging features of Othello’s syndrome.

The average age at onset of Othello’s syndrome was 68 (25-94) years with 61.9% of patients being male. Othello’s syndrome was most commonly associated with a neurological disorder (73/105) compared with psychiatric disorders (32/105). Of the patients with a neurological disorder, 76.7% had a neurodegenerative disorder. Seven of eight patients with a structural lesion associated with Othello’s syndrome had right frontal lobe pathology. Voxel-based morphometry showed greater gray matter loss predominantly in the dorsolateral frontal lobes in the neurodegenerative patients with Othello’s compared to matched patients with neurodegenerative disorders without Othello’s syndrome.

Treatment success was notable for patients with dopamine agonist induced Othello’s syndrome in which all six patients had improvement in symptoms following decrease in medication.

Wikipedia has a decent entry on morbid jealousy. I also found this good post at The Neurocritic The Tragedy of Othello Syndrome, which links to this 2010 review article, Othello Syndrome: Preventing a Tragedy when Treating Patients with Delusional Disorders. Here’s one example Neurocritic highlights from the review:

A married man, 43 years old, was first admitted to a mental hospital in June 1951. He complained of feeling “tensed up” as a result of the belief that his wife was unfaithful to him. Careful enquiries showed that there was not a scrap of evidence to support his suspicions, which began when a workmate allegedly asked him whether he had ever suspected his wife of having an affair with another man. His suspicions increased considerably when one day she failed to give what he deemed to be a satisfactory explanation for the origin of a smart pair of bootees in her possession. … Once, he attempted to strangle his wife but was stopped in the nick of time by the intervention of neighbors. Another time, he rushed scantily clad from the house in a fruitless attempt to catch his wife with a paramour.

The Dana Foundation highlights research by Richard Camicioli onNeuropsychiatric disorders: Othello syndrome—at the interface of neurology and psychiatry as one way to explain this pathology:

Dysfunction in the right frontal lobe may explain how a neurological problem can produce an apparent psychiatric problem such as Othello syndrome, according to Richard Camicioli, a clinical neurologist in the department of medicine at the University of Alberta…

The left hemisphere generates interpretations of experience that help us make sense of our experience, Camicioli said. The right hemisphere —especially the right frontal lobe —helps us to monitor our actions and detect anomalies.

This brain region performs the function of a fact checker, monitoring the interpretations of the left hemisphere for plausibility and accuracy. When the right hemisphere is damaged, the left hemisphere is free to issue interpretations that might make no sense.

One reason that Othello Syndrome caught my eye is because of two parallels. First, denial is a major problem in addiction. Furthermore, dysregulated dopamine transmission is a major part of addiction. Research has pointed to problems of frontal lobe dysregulation, alongside over-activation of mesolimbic dopamine, as central to addictive behavior. “Monitoring” breaks down, and delusions of denial might perhaps come into play.

There is a whole social side to denial which I won’t get into here. But what I want to point to is that frontal lobe regulation can be social regulation, and not simply monitoring. It deals with interpreting and judging social situations and partners. These parts of our brains are richly cultural, and also evolved through culture. So it’s no surprise to me that dopamine dysregulation produces tragic problems, much like we see in our great works of art.

The second reason Othello syndrome caught my eye is the intriguing parallels with frontotemporal dementia. I wrote a long 2010 post on Frontotemporal Dementia, Neuroanthropology, and Reverse Engineering the Mind, which examined the fascinating research in the book Language, Interaction, and Frontotemporal Dementia.

“FTD often presents with behaviors similar to psychiatric disorders, affective disorders, antisocial or aggressive behavior, as well as the prevalence of alcohol abuse (7).” Clinical diagnosis can also be difficult because most clinical tasks are cognitive assessments, and on which bvFTD patients often perform normally. bvFTD patients present behavior changes, not cognitive ones.

These changes fall into two domains: (1) abnormalities in social emotions and perceptions, and (2) changes in behavioral engagement. These changes are linked to atrophy in a range of brain structures. Early on, the frontoinsular, orbitofrontal and ventromedial cortices and anterior cingulate can be affected. As the dementia progresses, the right frontal cortex can show general atrophy in the ventral, medial, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, along with the temporal lobes, anterior cingulate, and insula.

With social emotions and perceptions, patients are “often seen as lacking social emotions like sympathy, empathy, shame, or guilt… Patients [can have a]lack of insight (i.e., unawareness of their behavioral changes) and lack of concern for others.”

Frontotemporal dementia is not the same at Othello’s syndrome, not at all. But the loss of appropriate social emotions, a corresponding lack of insight, and a problem characterized largely by behaviors – those are intriguing parallels. As these things get compromised, “delusions” from the other person’s point of view appear – a psychological explanation for what is largely a change in neurocultural processing. Suddenly, jealousy, disinhibition, and continued use just seem to make sense, particularly as people get on your case and you start to feel defensive… What might seem a lack of perception and insight from the outside might be better viewed as simply a subtly but dramatically altered way of acting and being social for people living in rich cultural environments and negotiating powerful affective relationships.

There are beguiling links between clinical aspects of Othello’s syndrome, denial in addiction, and frontotemporal dementia. Reducing these clinical aspects to merely neurological and psychological dysfunction misses a crucial point. The frontal lobes do cultural work, are immersed in that from birth and evolved in a matrix of handling social relations and negotiations. As we come to see these problems as potentially neuroanthropological disorders, we might come across new ways to understand their behavior and help them negotiate their social lives.