As long as Theresa May’s Conservative government is representing the UK at the Brexit negotiating table, Britain’s imperial past will continue to haunt its European withdrawal. The ghost that looms largest is none other than the prime minister’s “political hero” and “new lodestar”, Birmingham’s turn-of-the-century imperial protectionist, Joseph Chamberlain.

Like the early 20th century that Chamberlain lived in, the world has witnessed a resurgence of economic nationalism since the 2007 to 2009 recession. Britain, through Brexit, is leading this retreat from economic globalisation. The May government’s proposal to pursue an economic plan of “Britain for the British” after Brexit harkens back to Chamberlain’s bygone imperial age of Tory protectionism.

The battle over tariff reform

Against strong Tory opposition, in the 1840s Britain had adopted free trade, a policy of non-discrimination against foreign goods from all over the world. In 1846 Liberal radical free traders were successful in overturning Britain’s Corn Laws, high protective tariffs placed on foreign grain imports aimed at protecting domestic grain producers. The free traders succeeded in large part because of an effective propaganda campaign that put British consumers first. They argued that eliminating tariffs on foreign grain would bring the “cheap loaf” and so end an era marked by mass hunger and famine: the so-called Hungry Forties.

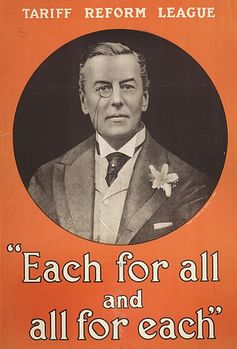

A poster of Joseph Chamberlain produced by the Tariff Reform League.

By the turn of the 20th century, Chamberlain was pushing for tariffs to be reimposed. From its inception in 1903, his Tariff Reform Movement gained steady momentum. Chamberlain and his followers decried Britain’s political and ideological adherence to free trade. Instead, they sought to tie Britain’s economic sails to the empire’s settler colonies, through preferential tariffs with Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Like today’s Brexiteers, Chamberlain’s nationalistic Tariff Reform campaign also advocated for anti-immigrant legislation and “Britain for the British”.

Eventually, Chamberlain and his conservative imperial protectionists were stymied owing to widespread opposition from British consumers and the political left.

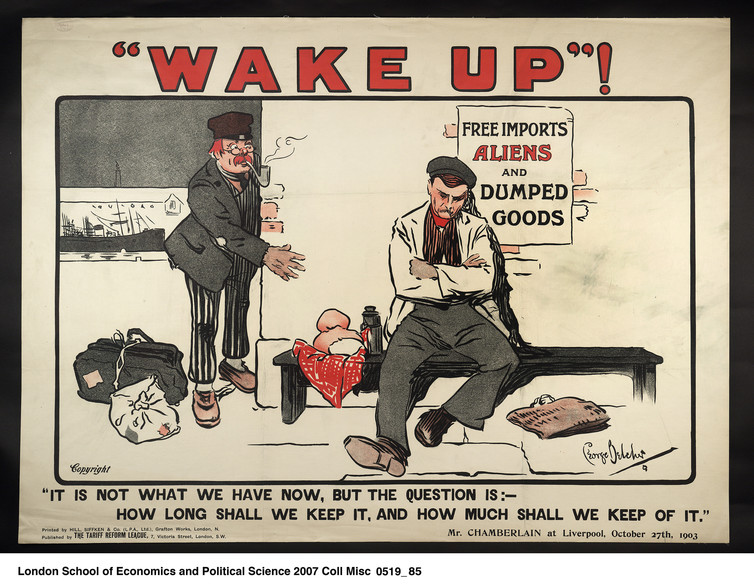

A poster produced for the Tariff Reform League in 1903. LSE Library

Borrowing from Chamberlain

Whether we call it the Anglosphere or Empire 2.0, May’s proposed Brexit programme wears the mantle of Chamberlain’s Tariff Reform Movement.

The May government, like Chamberlain, has once again asserted that the empire’s Commonwealth markets can provide the solution to the perceived problems wrought from open European migration and economic integration. Tories, nostalgic for the Empire, suggest that Brexit will clear the way for “a new federation” and preferential trade with the Commonwealth.

Today’s Brexiteers are also careful to avoid explicit protectionist terminology, in the same way that their imperial protectionist predecessors did. The May government has begun replacing reference to free trade with “fair trade”. As in Chamberlain’s days, this refers to raising tariffs in retaliation against nations that impose trade barriers upon British goods, or to giving preferential treatment to Commonwealth states.

The difference is for consumers

The May government has already promised to look after the British farming industry during Brexit trade negotiations. Its new industrial strategy includes state subsidies for British industries coupled with severe immigration restrictions on foreign workers at “every sector and every skill level”. It wants to turn away from European market integration (and so Britain’s largest trading partners), and turn instead to Commonwealth markets to bolster the export of British tea, jam, and biscuits, British consumers be damned.

In the early 20th century, free traders successfully undermined Chamberlain’s Tariff Reformers by running a concerted opposition campaign focusing on the British consumer. In the lead-up to the June 2016 Brexit referendum, by contrast, discussion about what leaving the EU would mean for consumers was notable only for its absence.

Missing was how Britain’s poorest would feel the sting the most – and how a post-Brexit declining pound, stagnated wages, and further increases in the price of basic food staples will only amplify the pain.

Rebirth of imperial nostalgia

In a final echo of early 20th-century debates over trade and empire, Brexit’s critics charge that leaving the EU will result in geopolitical discord: that Brexit threatens European and world peace. Defenders of British free trade similarly condemned Chamberlain’s Tariff Reform Movement in the years leading up to World War I. They charged that a British turn to imperial preference and retaliatory tariffs would only exacerbate international tensions, paving the way toward military conflict.

The era’s leading advocates of free trade such as Norman Angell, in his 1910 international bestseller, The Great Illusion, instead argued that a more economically interdependent Europe created a safer and more peaceful world. Their arguments helped defeat Chamberlain’s campaign.

Britain’s imperial past – a previous age marked by economic nationalism, beggar-thy-neighbour politics, hunger, and world war – haunts Brexit. Imperial nostalgia motivates the pro-Brexit protectionist pipedream of prosperity with its aim to cull migration and cultivate Commonwealth trade as a replacement for the European breadbasket next door.

![]() The ghost of Chamberlain doubtless is looking down and smiling upon May’s own Tariff Reform Movement – and with no small amount of envy. Because, with Labour supporting only a slightly softer Brexit, May’s tariff reformers will continue to trundle along with little opposition.

The ghost of Chamberlain doubtless is looking down and smiling upon May’s own Tariff Reform Movement – and with no small amount of envy. Because, with Labour supporting only a slightly softer Brexit, May’s tariff reformers will continue to trundle along with little opposition.

Marc-William Palen, Lecturer in History, University of Exeter