In a region of long-serving autocrats, any electoral power transfer is “historic” enough. By that standard, Angola’s legislative elections are a milestone for Central Africa because they mark the peaceful end of President José Eduardo dos Santos’ 38-year rule.

By sitting out this election, dos Santos allowed Angola’s opposition an opportunity – at least on paper – to vie for political power. In reality, the sheer entrenchment of dos Santos’s party, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), made it impossible for the opposition to claim an upset. In a multi-party contest on August 23, the MPLA easily won 150 of Angola’s 220 parliament seats, and Defence Minister João Lourenço will now take the helm. With the MPLA’s continuing dominance, Angolans can only expect cosmetic changes to their corruption-ridden political and economic life.

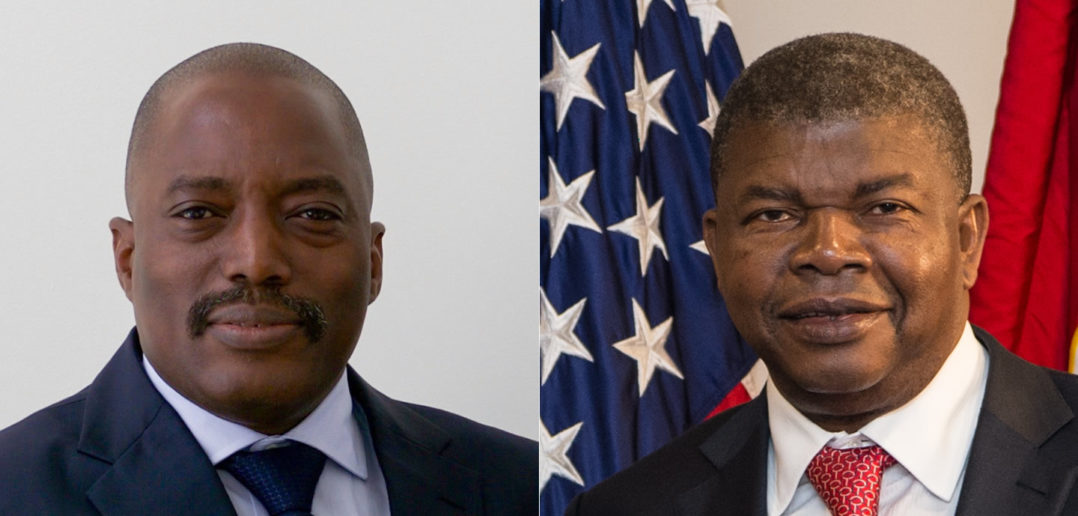

Lourenço’s election may have been predetermined, but the regional tensions he has to contend with are very real. Chief among them is the political crisis hovering above the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). President Joseph Kabila’s refusal to stand down has delayed elections to choose his successor, sparking deadly protests in Kinshasa and other cities. Kabila’s 16-and-a-half-year presidency legally ended in December 2016, but he has remained in power by claiming the DRC lacks the financial capacity to organise elections.

It is becoming increasingly clear that Kabila will not honour the deal, brokered with the opposition at the end of last year, which stipulated elections at the end of 2017 and Kabila’s subsequent departure. The agreement paved the way for the Congo’s first peaceful power transfer – a transfer that now remains up in the air thanks to the government’s “glissement” strategy.

There’s a distinction between Angola’s marginally democratic elections and the DRC’s moribund prospects for holding its own. But this contrast belies a deep-seated commonality shared by these countries: given their autocratic traditions, both remain at the mercy of weak and ineffectual institutions.

In their own ways, both Angola and the DRC demonstrate how protracted authoritarianism not only consolidates the power of ruling politicians but also renders institutions and the state itself dysfunctional. All the while, these authoritarians marginalise other forces that could legitimately offer the country a better future, as the supporters of Congolese opposition candidates are well aware.

In Angola, the uncontested reign of dos Santos and the MPLA for four decades has enabled despotism and cronyism on an industrial scale. The President’s children head Angola’s most lucrative state-owned corporations. Other dos Santos allies are reportedly major beneficiaries of the gains generated by Angola’s petro-economy, which they pour into real estate and other investments in Portugal. Such corruption breeds extreme social inequality. The cost of living in the capital city of Luanda outranks every other city in the world, including London, even as most residents live without formal housing or electricity.

With so much vested in the status quo, Dos Santos’s decision to step down only came after a series of actions calculated to ensure he would escape from prosecution. Institutional rules for checks and balances would have inhibited those manoeuvres, but there are few such rules in a political environment defined by three decades of civil war.

The Congolese state has an even bloodier history, with Kabila owing his position to his father’s forceful military takeover in 1998. The DRC’s internal conflicts continue to spawn militia forces that terrorise large swathes of its eastern territories. Kabila himself would argue it is unreasonable to expect a country with those circumstances, and no tradition of peaceful regime change, to easily handle an electoral power transfer.

However, Kabila is the one perpetuating the most recent crisis. The DRC urgently requires peaceful regime change to form a durable, legitimate government and enforce the rule of law. Failure to elect a new government may lead to another period of a brutal civil war. With Kabila trying to buy time and exploiting the relative lack of international pressure for his exit, the Congo’s future is now dangerously uncertain.

With political leaders resolute in their intransigence, can the Angolans and Congolese look to civil society for hope? The two country’s paths diverge here, and the country denied an election is ironically making the greater strides. In Angola, any substantive changes in the regime’s harsh approach to civic action don’t seem to be forthcoming. In the DRC, on the other hand, Kabila has unwittingly provided the impetus to a burgeoning pro-democracy movement.

United in their opposition to Kabila’s continued rule, Congo’s often-scattered opposition has coalesced behind a few key leaders. Chief among them is Moïse Katumbi, a popular former governor whose expected presidential bid enjoys strong public support. In a bid to eliminate his most potent rival, Kabila has forced his judiciary to pursue dubious charges against Katumbi, who now lives in exile in Belgium. Inside the country, a grassroots movement has kept up pressure: Congo’s Catholic bishops have used their influence to push Kabila to allow for Katumbi’s return, while opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi made a daring return to Kinshasa this week to call for a coalition that would force Kabila out by the end of the year.

A fully functioning democratic state often requires a long, painstaking history of incremental change, which both countries are only beginning to make. It would be a stretch to expect Angola’s Lourenço to deliver on his promises to tackle corruption in his own ruling system, but a peaceful transition to a post-Kabila DRC remains a tantalising possibility. Were it to take shape, one of Africa’s most conflict-ridden and impoverished countries would take an important step toward being a truly democratic republic – setting an important example for Angola but also the rest of the region.