Photograph by Kim Traynor

Police forces are taking up to 30% longer than two years ago to respond to emergency 999 calls in some parts of the country with forces blaming the impact on deep spending cuts, a Bureau report reveals.

The three-month investigation used Freedom of Information requests, interviews with police officers and an analysis of government data. It uncovered:

- Vital minutes have been added to the time it takes for a squad car to arrive at an accident or crime scene

- Just under a third of the police forces that collect response time information confirmed they reacted more slowly to emergency calls in 2012 than they did in 2010

- Some police force 999 emergency response times have increased by over 15%, with one force recording an increase of 30%

- Five police forces have changed their target times since 2010, giving themselves more time to respond to 999 call-outs

- A 23% increase between 2010 and 2012 in the number of calls not answered by the closest police force, but instead being bounced on to a neighbouring force

Such is the scale of the problem that in Bedfordshire, where the police force changed its targets in 2011 from a 10 minutes emergency response target to 15 minutes, a specific warning was put out to staff not to complain publicly about cuts as it risked reducing confidence.

The force’s recent Victim Satisfaction survey had thrown up comments that ‘Officers who attend [incidents]are making ill thought out comments such as making reference to the number of incidents they have to attend and the lack of officer numbers.’

The email, which was has been leaked to the Bureau, goes on to say: ‘Can you please ensure that the message is briefed out that this is unacceptable and is shedding us in an unprofessional light… I fully appreciate that we are all concerned with diminishing resourses [sic]and external pressures, however by adjusting this behaviour we will quickly improve on this aspect of victim satisfaction.’

On coming to power, the coalition ordered police forces to cut their budgets by 20% between 2011 and 2015. The number of police officers has reduced by 10,000 since 2010, according to government figures, with fewer members of the police today than at any other time in the last decade.

The reduction in civilian police staff has been even greater. Over 12,000 support staff were lost between 2010 and 2012, nearly 16% of their total number.

The recent spending review for 2015/16 announced a further reduction in the police budget in real terms of 4.9%.

Peter Neyroud, research associate at the Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford and specialises in policing, said: ‘While some of these forces have just increased their response rates by fractions of a minute these are annual averages and could be masking some serious lapses. The top responsibility of the police is to save lives, and so they ought to be prioritising that and ensuring that they have sufficient units to cover getting to emergency response call outs.’

Responding to Emergencies

The Bureau’s investigation showed that 57% of the police forces in England and Wales that record their response times (16 out of 28 forces) reported that in 2012 they took longer to respond to emergencies than they did the year before.

Of the 25 forces with figures going further back to 2010, 7 said their response time had slowed.

Emergency 999 calls are first answered by an operator before they are patched through to the correct service. Once the call reaches the police the call is graded as emergency, priority or non-emergency.

As well as many reporting an increase in their response times to emergency calls, two thirds of forces also reported an increase in the time it took them to get to ‘priority calls’ in the last year.

At one of the forces with the worst record, Assistant Chief Constable Robin Merrett of Sussex police, which has seen three minutes added to its 2010 average response time of 10 minutes, admitted performances had declined amid a ‘challenging programme of modernisation and savings’. He said: ‘Sussex Police acknowledges that since 2010 there has been a decline in the numbers of emergency and priority calls that are responded to within 15 minutes.

‘This period has seen a 10% increase in the number of calls that needed a grade 1 emergency response. At the same time the force is delivering a challenging programme of modernisation and savings.

‘We are aiming to put in place changes that will save money without the quality of services suffering. Many aspects of our service have been maintained and some have even improved. This is obviously not the case in respect of response calls and we will be looking at ways that we can improve our response to emergency and priority calls.’

Get the data: 999 response times

Fewer staff and resources are two of the reasons offered by police officers for the increases in call-out times. However, with overtime budgets also being cut, some insiders have also suggested that a lack of motivation on behalf of officers may have an impact on response times.

Shaun Brady, a retired officer from Merseyside, explained how changes to overtime pay were affecting some officers’ attitudes towards call-outs. ‘You’d see it in the response sections,’ he explained, ‘if they were called to a burglary or an assault and they were going to go over their shift, they’re being told no overtime, so they’d have to hand the case over and not get the arrest. So instead you’d see officers coming to the end of their shifts and just shadowing other officers, or working out ways to avoid responding.’

Targets

Each force sets its own targets for how long it should take them to respond to 999 emergencies. FOI requests to all forces in England and Wales revealed that over the past three years five police forces have changed their targets – allowing them more time to arrive at an emergency.

The Metropolitan police changed its response targets in April 2012, moving the time limit for responding to 999 emergencies from 12 minutes to 15 minutes. At the same time, however, it increased the number of call-outs to be met within this time from 75% to 90%.

The force claims this sets a more challenging target. A spokesperson said: ‘We will continue to aim to achieve and exceed the targets that we have set.’

Bedfordshire also changed its targets in 2011 from a 10 minutes emergency response target to 15 minutes, in urban areas.

Compounding the problem, Bedfordshire recently shifted to working from regional hubs rather than local stations, meaning in some cases even the revised response times are not being met, according to Jim Mallen, a Detective Sergeant and Police Federation representative.

‘It is the rural areas that are suffering,’ explained Mallen, ‘we’ve moved to two hubs in Bedfordshire with miles between them. So now travelling time to areas in between those hubs, even with blue lights on would be 20 minutes.’

West Midlands, Kent and the City of London police have also changed their targets since 2010. Kent scrapped its targets completely in August 2012.

A spokesperson said, ‘Kent Police has not had targets for attendance times since autumn 2012. What matters is attending calls as quickly and safely as possible, and the quality of service when officers attend an incident.’

Oxford Criminologist Neyroud explained that despite much research there has been no set ideal target time for emergency call outs. But, he says, ‘If times are changing because the previous targets were being missed then that is absolutely wrong.’

‘Given that tier 1 emergency calls can be in life threatening cases, then that is wholly inappropriate.’

Emergency Calls

Emergency 999 calls are patched through from a central operator, most often BT. If the call is not answered by the police staff that call is then bounced to another telephone line or a different police force. Those bounced calls are logged as ‘abandoned’.

An abandoned call means it takes longer to get a message through, longer to dispatch police officers to an emergency and increases the risk of the caller hanging up before the call can be answered.

In 2012 there were 11,707 more abandoned 999 calls than two years earlier, a rise of 23%.

The Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) has set guidelines for abandoned calls, recommending that the number should not exceed 2% of a force’s total calls.

However, last year six police forces registered having an annual average of abandoned calls over 2%, with many more overstepping the target on at least one month.

According to an FOI response West Mercia police force missed the 2% target every month last year save one. In 2012 Devon and Cornwall recorded an annual abandonment rate of 6.15%. In 2010 its rate was just 0.5%.

Devon and Cornwall has lost 250 administrative and support staff since 2010, 14% of its workforce. According to the force, 18 of those were from the call centres.

Get the data: Abandoned call rates

Northamptonshire Police Chief Commissioner Adam Simmonds was so shocked by the number of abandoned calls in his area that he commissioned a report into the issue, even though the force’s annual average never rose above the 2% guidelines.

The report ‘A scrutiny into call answering and handling’, charts the budget cuts and staff reductions in the Northamptonshire force during 2011 and 2012, and shows they directly correlate to an increase in 999 calls being abandoned and 101 calls going unanswered.

The force had used a commercial electronic work force management system to calculate the bare minimum number of staff to man the phones, cutting the equivalent of more than 20 full-time posts. Simmonds’ report notes that employing a strategy designed for commercial call centres had not translated to the needs of a police centre.

Cars

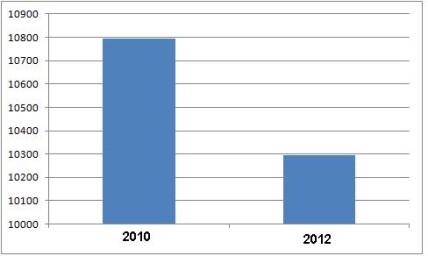

The number of operational vehicles available to the police has dropped by 500 units since 2010, or one in twenty vehicles.

Again, forces have been affected differently and Dyfed-Powys and Northumbria police forces have both seen the number of vehicles available to them drop by more than 20%. Dyfed-Powys said it does not record 999 response times but Northumbria reported that it was taking longer to respond to both emergency and priority call-outs in 2012, than it had two years earlier.

Get the data: Operational response vehicles

In Devon and Cornwall, which lost nearly 10% of its fleet, the Police Federation report that the force is closing its police owned workshops so its cars now go to commercial garages. ‘That will cost more money in the long run,’ said the area’s Police Federation chairman Nigel Rabbitts.

Operational vehicles available to police in 2010 and 2012

Steve White, vice-chair of the Police Federation of England and Wales, said: ‘We have long been saying that you only get one thing for less and that is less. While we recognise that efficiencies should always be sought it is very difficult to see how services in their entirety can be maintained with significantly fewer resources. Whether it results in the phone call to police taking longer to answer, the closure of a local police station or having to wait longer for a police unit to arrive, this is where the difference will be noticed.

‘Yes crime statistics are falling but you’ve got to bear in mind that in some cases people can’t get through on the phones, and there are less officers proactively patrolling, so fewer crimes get detected and reported,’ he added.

Shadow home secretary, Yvette Cooper, said the Bureau’s revelations were ‘very worrying’. She said, ‘These figures show the service the police provide to the public is being hollowed out.

The police are doing what they can, but the scale and pace of the government’s cuts over the last three years is hitting services despite Theresa May’s promises that the front line would not be hit.

‘People want to know the police will be there when they need them. Because of this government’s economic failure the problem is likely to get worse, with fewer officers travelling further to incidents.

A Home Office spokesman said: ‘Police reform is working and recorded crime is down by more than 10% under this government. Like all parts of the public sector, the police must play their part in helping to tackle the deficit, but there is no question they still have the resources to do their important work.’

Written by Maeve McClenaghan