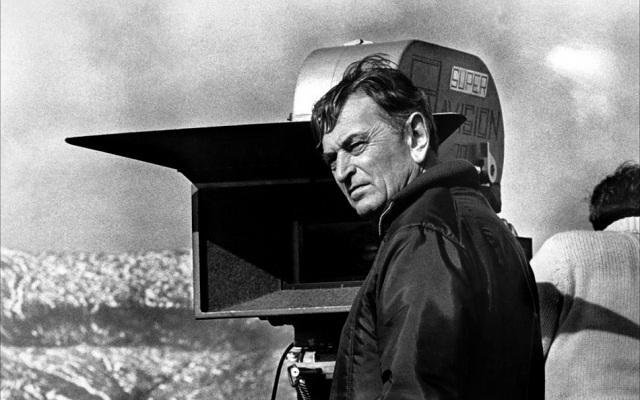

With a special 50th Anniversary Lawrence of Arabia Blu-Ray out this week and a restored cut of the timeless epic being given a cinematic re-release later this month, it seemed like an opportune time to take a glance back at the work of legendary English director, David Lean.

Lean was brought up by very strict Quaker parents and wasn’t even allowed to watch movies until he was an adult. Once he was of age though, he made up for lost time and fully immersed himself into cinema. He managed to get a job as a teaboy at Gaumont Studios before working his way up to clapperboy and ultimately on to third-assistant director. He eventually became an editor at the studios and would go on to edit Powell and Pressburger’s 1941 classic 49th Parallel. It has long been said that it was this grounding in editing which contributed to Lean’s seemingly mechanical like understanding of how a film should look and piece together.

Despite his directorial career spanning some forty years, from In Which We Serve (1942), to A Passage To India (1984), Lean only ever made sixteen films. Yet from his early romantic melodramas and Dickens adaptations, right through to the lavish and sweeping epics of his later years, Lean’s pictures became a byword for quality. His unflinching attention to detail and masterful eye for a shot, has led him to create some truly historic cinematic moments. Lean knew how to evoke a mood and crate an atmosphere through his film, from the tearful final goodbye in Brief Encounter, to the sight of Omar Shariff arriving out of the shimmering sunset in Lawrence of Arabia. Every shot was immaculately and very purposefully constructed. Lean was a director who stamped his own personal idea on every film he made, unflinching from his vision of how a film should look.

Lean is held in great reverence by fellow filmmakers, including the new-wave of Hollywood movie brats such as Spielberg and Scorsese, perhaps far more so than he is by critics. Not that he isn’t admired by some critics as well; it’s just that his love of the art of filmmaking and his dedication to the process itself has seen him become an undoubted filmmaker’s filmmaker. He remains one of Britain finest cinematic exports and a he has an impressive seven films in the BFI Top 100 British Films list, with four of these appearing in the top eleven. Add to this a CBE and the fact that he is only one of three non-Americans to receive an AFI lifetime achievement award, and you get a sense of how deeply respected he was.

Let’s take a look now and some of the choice cuts from his relatively small but enviable filmography.

Brief Encounter (1945)

Adapted from Noel Coward’s one-act play ‘Still-life’, Brief Encounter tells the story of two married people, Laura and Alec, who share a series of emotionally charged meetings before realising their relationship can never truly be anything more. This was at a time when moral values were such that the thought of a woman engaging in an extra-marital affair would be nigh-on unthinkable. The sanctity of marriage was rigorously clung to and even divorce was extremely rare. Laura and Alec both love each other deeply, but cannot bear to tear their own families apart.

Adapted from Noel Coward’s one-act play ‘Still-life’, Brief Encounter tells the story of two married people, Laura and Alec, who share a series of emotionally charged meetings before realising their relationship can never truly be anything more. This was at a time when moral values were such that the thought of a woman engaging in an extra-marital affair would be nigh-on unthinkable. The sanctity of marriage was rigorously clung to and even divorce was extremely rare. Laura and Alec both love each other deeply, but cannot bear to tear their own families apart.

The bittersweet romance is gloriously rendered in crisp monochrome, with the closing scenes at the railway station, as the steam swirls and the ill-fated couple realise they will never be together, a particular highlight. It does appear very dated now, the clipped accents and of its time dialogue especially, but Lean captures the heartbreaking nature of the situation perfectly. The scene towards the film’s end when their emotional goodbye is interrupted by a chatterbox friend of Laura’s, is filled with unspoken longing and minute gestures indicating the inner pain of the central couple.

Great Expectations (1946):

Lean’s first foray into the works of Charles Dickens remains perhaps the finest film adaptation of the great author’s works to date. Lean’s own Oliver Twist (1948) was also highly regarded, but its Great Expectations which has stood the test of time even better. For anybody who is unaware of the source material, Great Expectations charts the rise from rags to riches of young Pip, a boy from a poor family who comes into considerable wealth at the behest of a mysterious benefactor. The story follows his coming of age and ascent into manhood and alo charts his obsession with the beautiful but cold Estella.

Lean’s first foray into the works of Charles Dickens remains perhaps the finest film adaptation of the great author’s works to date. Lean’s own Oliver Twist (1948) was also highly regarded, but its Great Expectations which has stood the test of time even better. For anybody who is unaware of the source material, Great Expectations charts the rise from rags to riches of young Pip, a boy from a poor family who comes into considerable wealth at the behest of a mysterious benefactor. The story follows his coming of age and ascent into manhood and alo charts his obsession with the beautiful but cold Estella.

From the film’s opening on the desolate Kent marshes, Lean appears to have captured Dickens’ tone and his sentiments perfectly. In the unsettling scene where Pip first meets the escaped convict Magwitch, Lean captures the sense of danger and foreboding exactly as one might imagine after reading it in the book. Another such moment occurs later on when Pip first visits the unhinged old spinster Miss Havisham. The eerie haunted house vibe which Lean creates thanks to his mastery of lighting and camera angles is exceptional. The black and white photography is superb throughout and Lean seamlessly blends the story’s romantic moments with its sinister dark undertones.

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957):

A truly classic war movie which won Lean his first ever Oscar. The Bridge on the River Kwai also saw Lean reunite once again with Alec Guinness, one of the director’s most regular collaborators. Set in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in Burma in 1943, the film revolves round the battle of wills between Camp Commander Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa) and Colonel Nicholson (Guinness). Saito wants Guinness to force his men to build a railway bridge which would then be used to transport Japanese weaponry. At first Nicholson refuses but he finally relents and sees it as a morale-boosting project for his beleaguered men. As the building goes on, Nicholson grows obsessed with completing it to perfection and begins to lose sight of its ultimate purpose.

A truly classic war movie which won Lean his first ever Oscar. The Bridge on the River Kwai also saw Lean reunite once again with Alec Guinness, one of the director’s most regular collaborators. Set in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in Burma in 1943, the film revolves round the battle of wills between Camp Commander Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa) and Colonel Nicholson (Guinness). Saito wants Guinness to force his men to build a railway bridge which would then be used to transport Japanese weaponry. At first Nicholson refuses but he finally relents and sees it as a morale-boosting project for his beleaguered men. As the building goes on, Nicholson grows obsessed with completing it to perfection and begins to lose sight of its ultimate purpose.

Full of eye-catching cinematography, as one might expect from a Lean epic, there’s also a deep psychological aspect to the film too with various cultural and class divides rife throughout the picture. At the centre of the story though is Guinness’s bravura performance as the incredibly heroic and yet seemingly increasingly demented Colonel. Throughout the movie, Lean paints a vivid picture of wartime struggle, of military duty and of British stiff-upper-lips.

Lean pulled off a feat he would repeat again with his other ‘epic’ movies by meshing together both a sweeping and grand story with very personal character developments. In this instance, the end result was a tense and thrilling adventure that has quite rightly become a landmark war movie. Interestingly, such was the cultural impact of the film, its theme tune , ‘Colonel Bogey’, famously whistled in the movie by the defiant captured soldiers, was actually played at Lean’s memorial service at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

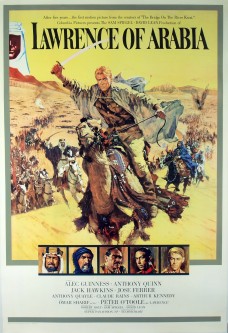

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Arguably Lean’s greatest masterpiece of all, Lawrence of Arabia is truly a special piece of cinema. The term ‘epic’ gets used far too readily in some cases, but if ever there was a film that warranted the tag, it was this one. Lawrence of Arabia is a film not only ambitious in terms of its length, running to around 216 minutes, but also in terms of its concept and execution. The extensive story combines visceral action and sun-kissed adventure, set against some truly stunning scenery and focused upon a charismatic but deeply flawed hero.

Arguably Lean’s greatest masterpiece of all, Lawrence of Arabia is truly a special piece of cinema. The term ‘epic’ gets used far too readily in some cases, but if ever there was a film that warranted the tag, it was this one. Lawrence of Arabia is a film not only ambitious in terms of its length, running to around 216 minutes, but also in terms of its concept and execution. The extensive story combines visceral action and sun-kissed adventure, set against some truly stunning scenery and focused upon a charismatic but deeply flawed hero.

Peter O’Toole was perhaps never better than his performance here, and partial credit must go to Lean for coaxing such a performance out of him. Lawrence was a conflicted and contradictory character, torn between his compassion and his sadomasochistic streak that saw him so attracted to war. Lean also brought out the very best from a magnificent supporting cast including Omar Sharif, Claude Raines, Alec Guinness and Anthony Quinn. Along with O’Toole’s extraordinary performance, the manner in which Lean and his cinematographer Freddie Young captured the unforgiving vastness and yet the stunning beauty of the Arabian desert, was a crucial part of making Lawrence of Arabia the masterpiece that it is. Scenes such as the aforementioned moment where Sharif’s Sherif Ali emerges from the horizon and slowly makes his way out of the heat gaze towards an awestruck Lawrence, is majestic in its beauty and a triumph of patience and attention to detail. Likewise, when watching the exhilarating scene where Lawrence and his army ambush a train in the desert, one can only admire the sheer scope of what Lean was able to achieve.

Lean’s film was far being just a series of glorious looking set pieces however. It also focused on capturing a certain mood and a genuine sense of place. Part of what makes it so brilliant is how effectively it is able to immerse the viewer in these obscure and distant events in the sweltering Arabian Desert. Lean delivered a visually stunning and utterly captivating piece of cinema.

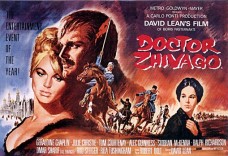

Dr. Zhivago (1965)

Another visually striking epic from Lean, Dr Zhivago is a sprawling romantic drama set against the backdrop of the First World War and then the Russian Revolution. Painstakingly designed and containing typically luscious scenery, it also possessed a career-defining central role for Omar Sharif.

Another visually striking epic from Lean, Dr Zhivago is a sprawling romantic drama set against the backdrop of the First World War and then the Russian Revolution. Painstakingly designed and containing typically luscious scenery, it also possessed a career-defining central role for Omar Sharif.

To try and summarise the complete plot of Zhivago here would be far too difficult, so in very brief terms, the film follows Yury Zhivago, a physician who is torn between two women as the tumultuous course of Russian history sweeps ever onwards. As one might imagine in a film developed from a weighty Russian novel, there are various plot strands and characters intertwining throughout the film but Lean keeps a keen eye on them all and manages to keep you engaged in each one.

It is another especially long movie, clocking in at nearly 200 minutes depending on what version you are watching, but as became Lean’s trademark, the film never feels anything less than fluid throughout. It perhaps struggles slightly under the weight of being Lean’s follow up to Lawrence of Arabia, and while it doesn’t quite possess the same spirit of adventure, and neither Julie Christie or Omar Sharif possess the charismatic brilliance of Peter O’Toole, it is nonetheless still an engaging and visually absorbing film.

Also Worth Seeking Out:

Oliver Twist (1948)

Hobson’s Choice (1954)

Ryan’s Daughter (1970)

A Passage to India (1984)