The state of the UK economy featured heavily in the election campaign, but the discussion was overwhelmingly focused on the deficit. Over the next five years, however, the new government will have to confront a range of economic challenges. Predicting how these will develop is notoriously difficult (although opinion pollsters may now have a worse reputation than economists for forecasting), but several key areas can be identified – and restoring growth to the UK economy is of paramount importance.

The outlook for the next few years still points to relatively slow growth. After an upturn in 2014, indications so far point to slowing growth in 2015. The service sector saw lower growth, whilst manufacturing output remains below pre-crisis levels. In their most recent Inflation Report, the Bank of England has revised down its projections for growth in 2016 and 2017.

Headwinds

There are several potential headwinds that may slow potential growth. The major persistent problem in the UK economy has been its weak productivity performance. This is central to any sustained growth in the economy and living standards – and, from this, any rise in government revenues to reduce the deficit. The outlook for the UK in the context of the global economy must therefore be considered from this starting point.

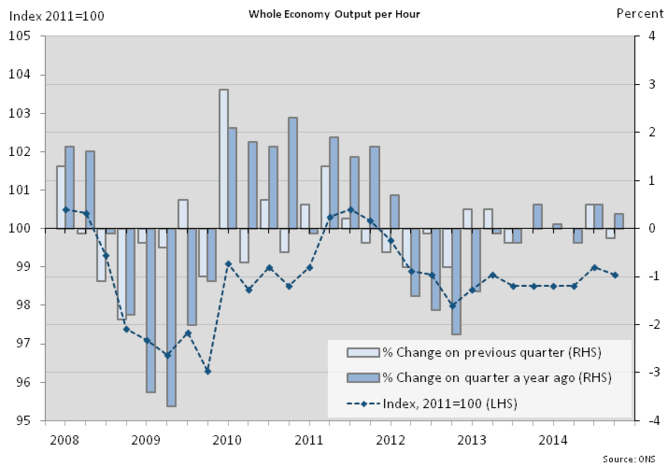

Probably the largest challenge is the UK’s recent poor productivity performance. As the graph below shows, labour productivity fell sharply during the period following the 2008 financial crisis, and has only risen fitfully since so that it remains below pre-crisis levels. Such a prolonged absence of productivity growth is virtually unprecedented during peace time.

The growth of the economy is critically dependent on productivity performance. Living standards are only likely to rise without this through favourable external developments (like the recent fall in oil prices) and this is unlikely to produce a sustained improvement. The stronger growth is, the faster the deficit will come down and the more room for manoeuvre the government would have with taxes and spending.

There is no clear agreement over what lies behind restoring growth, however – nor what the government can do to address it. In the first place, as the International Monetary Fund has noted, similar trends can be observed across developed economies. This has recently given rise to suggestions that advanced economies may be facing “secular stagnation”, where the new normal is one of persistently lower growth rates than these countries experienced in recent decades.

Workers and wages

Normally we would expect recoveries from a recession to be associated with productivity growth as idle capacity and under-employed workers are put back to work and firms raise their investment. Several factors appear to have inhibited this and which may persist. Despite low interest rates and profitability close to pre-crisis levels, company investment remains subdued – indeed business investment fell in the first quarter of 2015. There are a number of possible reasons for this. The fall in real wages since 2008 has made labour relatively cheap and thereby reduced incentives to add capital. The continued subdued outlook for demand in the economy also leads to sluggish investment.

There are other possible reasons why forces for productivity growth may not be operating as normal. Productivity growth is sustained through transferring labour and other resources from low productivity areas of the economy to expanding, high productivity ones. On both sides of the equation, this may have been inhibited in the UK.

On the high productivity side, fragility in the financial sector may have undermined the willingness to extend funds to risky, but potentially productive, new ventures. On the other side, it has been argued that low wages and borrowing costs have allowed low productivity “zombie firms” to remain in business and thereby inhibit the transfer of resources to higher productivity activities. A report by the innovation charity Nesta found that those start-up firms that have been formed since the financial crisis made no net contribution to productivity growth, while a significant number of productive firms went out of business.

The Bank of England Inflation Report, along with other analysts, attributes the weak productivity performance in part to growth in relatively low skilled employment. Worryingly this may be a half-truth. There has been considerable growth in relatively skilled employment, and labour composition – roughly speaking the quality of the labour force reflecting its education and skills – has made a positive contribution to productivity in this period. So productivity performance would have been even worse without this improvement in the quality of the workforce.

Supporting growth

There do appear to be some policies governments can undertake to support productivity growth; recent IMF research points to the key roles of competition, application of skilled labour and investment in information and communications technology and higher investment in innovation (research and develoment). Although the UK may be doing quite well on aspects of this, its investment in research and development remains low. Interestingly the IMF study finds no significant evidence linking labour market flexibility with productivity growth, although the Conservatives continue to emphasise the benefits of policies supporting this.

The major up-side of sluggish productivity has been that employment has remained high and unemployment has continued to fall (although with considerable variation between regions and groups of the workforce). Low wages have helped to sustain this employment, as the graph below shows.

Nevertheless, rising real wages would be expected to underpin any recovery. They are central to rising living standards and, from this, sustaining private consumption without household debt levels rising further. Through rising income tax receipts they are also required to reduce the budget deficit.

An up-turn in wages has been expected for some time and the most recent data does point to wages picking up. Nevertheless, the most recent survey evidence continues to point to modest wage growth.

Monetary policy

The recovery since the financial crisis has owed much to expansionary monetary policy as the Bank of England has maintained record low interest rates. It has, though, signalled that interest rates are likely to rise over 2015. Several developments point to this: the Bank of England sees remaining slack in the economy being eliminated with continued growth.

Also inflation remains in the highly unusual position of being below the Bank’s mandated target range, partly from slow wage growth, but it is expected to pick up. Plus, bond markets across the world have recently seen rises in longer term interest rates. This creates potential risks for the household sector – household debt has been rising and the OBR expects to see households experience rising debt levels relative to their income.

Cuts and spending

Enough was written during the election campaign about the role of fiscal policy. Oxford economics professor Simon Wren-Lewis has estimated how much austerity in the Coalition government held back UK economic growth. The IFS examination of parties’ manifestos pointed to ambiguities in the Conservative’s plans to achieve predicted cuts and expenditure commitments while eliminating the deficit. It is particularly difficult to predict what the fiscal stance of this new government will turn out to be and whether this will make a positive or negative contribution to recovery.

Trade performance

I have written elsewhere of the parlous state of the UK’s balance of payments. It is not just the weakness of trade performance, net investment income from the rest of the world has turned sharply negative. There are some positive signs in the external position, particularly growth in the US and signs of improved performance in the eurozone (although quantitative easing there may lead to sterling strengthening against the euro).

Nevertheless, both the Bank of England forecasts and the Office for Budget Responsibility point to only modest contributions from net exports and continued weakness in the UK’s trading performance. A key factor in the near future here will be the EU referendum. The lead up to it is likely to generate uncertainty, particularly unfortunate for a country that needs to attract capital inflows to finance its current account deficit. Moves to bring the referendum forward, particularly with opinion polls pointing to a likely vote to remain in the EU, may limit the negative effects of this.

The UK economy has recovered slowly from the worst downturn since at least the great depression. Productivity performance remains weak, although there is evidence that the workforce skills and education are growing. By historic standards projected growth is not particularly impressive, but this may reflect the new normal in advanced economies.

For some time forecasts from the Bank of England, the OBR and others have projected a recovery in investment and, with this, productivity and real wages. For this to materialise, business investment needs to rebound strongly. Yet, downside risks remain, particularly to the balance of payments and the household sector.

Jonathan Perraton is Senior Lecturer in Economics at University of Sheffield.

![]()