Photograph by Breahn Foster

Trauma. We often think of it as some event from the outside that hits us. That traumatizes us, leaving both immediate and lingering wounds. Like a gunshot to the heart or a knife to the belly. Something that decenters us, leaving not just physical wounds but existential ones that never heal.

New research points us in a different direction, one of “Trauma Socialized.” Less injury and more context, where trauma itself becomes mutable, not a bullet or a knife but a social event formed by social interactions and cultural meanings.

The journalist David Dobbs writes in the New York Times on the work of Paul Plotsky with rats and Brandon Kohrt with child soldiers with his article A New Focus on the ‘Post’ in Post-Traumatic Stress – Understanding the Effects of Social Environment on Trauma Victims.

It turns out that most trauma victims — even survivors of combat, torture or concentration camps — rebound to live full, normal lives. That has given rise to a more nuanced view of trauma — less a poison than an infectious agent, a challenge that most people overcome but that may defeat those weakened by past traumas, genetics or other factors.

Now, a significant body of work suggests that even this view is too narrow — that the environment just after the event, particularly other people’s responses, may be just as crucial as the event itself.

This expanded view of stress and trauma was on full view at the Culture, Mind, and Brain conference last October, put together by the Foundation for Psychocultural Research and UCLA. I organized the session on stress, trauma, and resilience that featured Plotsky and Kohrt, as well as anthropologist Lance Gravlee on race and stress and psychologist Carol Ryff on aging and stress. The talks by Plotsky, Kohrt, and Gravlee are in a new video I have included at the end of this post, along with a full set of links to conference coverage.

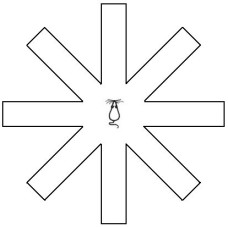

Radial rat maze devised by Dr. Plotsky

His latest work questions deeply the assumed “natural” impact of extended separation. The social environment in combination with maternal behavior is as determinative in shaping the impact of separation as the separation itself. As Dobbs writes:

About five years ago, Dr. Plotsky was thinking about the mother’s post-separation panic when, he said, “it hit me: maybe she views her environment as unsafe” because she and her pups are back in the same cage as the one they were taken from.

So he upgraded the simple cage to a complex one: a maze devised to test rats’ navigational skills. The separated rat family now reunited not in the kidnapping site but in the antechamber of an eight-room condo.

Now, even after 180-minute separations, things went fine. The mother would sniff the pups, check out a couple of rooms, then move everybody to one of them and coddle and nurse the pups much as she would after a 15-minute absence. Even if Dr. Plotsky separated the family again the next day (or even eight days in a row), she would do the same thing, usually choosing a new room.

But maybe the pups still suffered? Actually, no. Few showed any signs of trauma, either immediate or lasting. A separation that had been considered permanently scarring proved routine simply because the mother, having a more varied, secure environment in which to receive her pups, felt calmer and more in control, and she passed that on to the pups. Trauma seemed now to rise not from the separation alone but from the flavor of the reunion.

Similarly, the work of Brandon Kohrton child soldiers in Nepal shows how reintegration into the community matters greatly in whether being a child soldier ends up as something traumatic or not. Treated as pariahs, or put back in the same excluded class as before the war, and children who were soldiers do badly. Welcomed back into the community, the former child soldiers do well. Again, David Dobbs:

Since 2006, Dr. Brandon Kohrt, a psychiatrist and medical anthropologist at George Washington University, has followed the fates of Nepalese children who returned to their villages after serving with the Maoist rebels during their country’s 1996-2006 civil war… Their postwar mental health depended not on their exposure to war but on how their families and villages received them.

In villages where the children were stigmatized or ostracized, they suffered high, persistent levels of post-traumatic stress disorder. But in villages that readily and happily reintegrated them (usually via rituals or conventions specifically designed to do so), they experienced no more mental distress than did peers who had never gone to war. The lasting harm of being a child soldier, it seemed, arose not from the war but from social isolation and conflict afterward.

Thankfully, the Foundation for Psychocultural Research filmed both Plotsky and Kohrt in action at the Culture, Mind and Brain conference. You can get the full version of their research, and what it means for interdisciplinary work, in this video. I introduce the speakers, who also include Lance Gravlee and his equally ground-breaking work on the social construction of race and how that shapes the impact of stress and social inequality.

Here are your links, including previous coverage of the Culture, Mind and Brain conference and some of the speakers there.

–Culture, Mind and Brain Website

-YouTube Conference Talks on Stress and Trauma

-David Dobbs NYT Story on Trauma

-Day One Conference Post – Human Diversity, Genetics and Epigenetics, and On Being Interdisciplinary

-Day Two Post – Stress and Trauma, Culture and Cognition, Trauma in View, and Pathways to Interdisciplinarity

-Tanya Luhrmann’s conference talk on schizophrenia and hearing voices cross-culturally, which provides a wonderful demonstration with mental health of the same sort of dynamics discussed by Dobbs – the social matters in the psychiatric

-Post on Lance Gravlee and his work on race, genetics, stress, and inequality

-Carol Ryff interview on well-being and aging

Written by Daniel Lende