The “Mississippi baby” – a child who generated a great deal of excitement last year after being seemingly cured of HIV – now has detectable levels of HIV in the blood, according to doctors and health officials. The viral replication was discovered during a routine check-up after more than two years of not taking antiretroviral therapy without sign of viral infection.

The now four-year-old girl was now thought to be free of HIV after she was placed on a powerful three-drug cocktail of antivirals for 18 months immediately after her birth. Five months after stopping treatment with no detectable HIV levels or HIV-specific antibodies led to her being called the first person to be “cured” of HIV.

The new developments from the clinic are clearly disappointing for the child and her family, but also for HIV researchers, says a report by STDAware. It casts doubt on the hope for a cure in a similar situation in California, where a HIV-infected baby is currently being given the same course of treatment and seemingly HIV-free after nine months.

The story also calls into question a clinical trial planned by the National Institutes of Health involving more than 700 other HIV-infected infants, where the children were to be given intensive treatment from birth and then taken off treatment altogether after two years, because in the light of the Mississippi baby this could now be seen as unethical.

HIV reservoirs

With all this in mind, it is easy to consider the Mississippi case as a failure in the HIV field. But while it will certainly be a blow to the scientists directly working on the case, it is important to remember that small numbers of HIV-infected cells often survive antiviral treatment and therefore the likelihood of viral activation later in the child’s life was always a possibility. Instead of seeing this as a failure it should be thought of more as a set-back – the treatment did manage to make the virus retreat so far as to be undetected in tests.

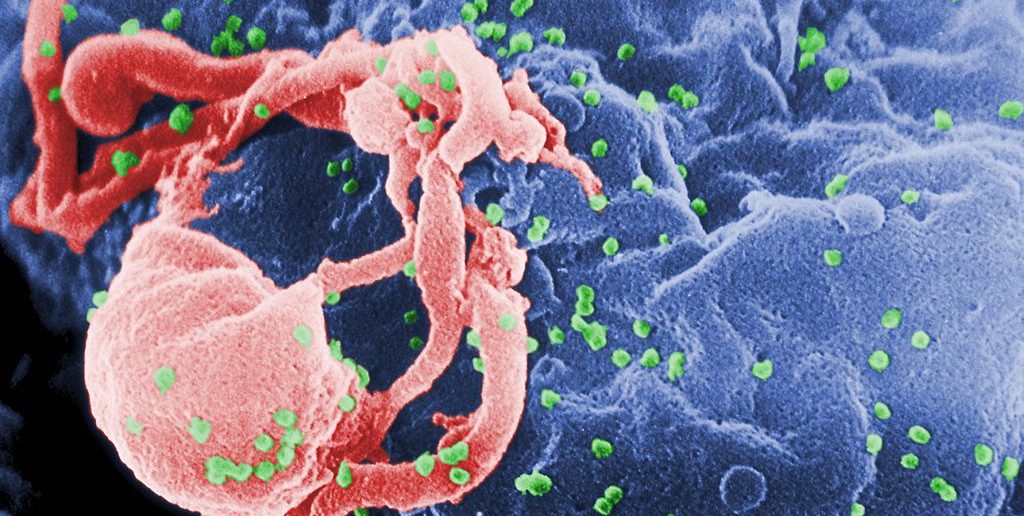

Indeed, a new study published in Nature suggests that HIV may establish itself in reservoirs substantially earlier than previously thought. The presence of these reservoirs is one one of the reasons that HIV has been so hard to eliminate. After infection, HIV inserts its genetic code into infected cells creating a pool of inactive HIV virus that is hidden from the immune system and that can also avoid antiretroviral drugs.

The researchers said that in rhesus monkeys, the viral reservoir of SIV (the monkey version of HIV) was established “strikingly early” in the first few days of infection and before the virus was detectable in the blood. Dan Barouch, professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and senior author of the study, said in light of the Mississippi baby their findings emphasised “the need to understand the early and refractory[resistant]viral reservoir that is established very quickly following HIV infection in humans”.

An unprecedented retreat

The Mississippi baby case is still hugely important and it is the details of the study that should be taken into consideration now. For example, the fact that the child was off antiretroviral treatment for two years and managed to maintain the virus in a quiescent state for this length of time is unprecedented – and much longer than the Nature researchers found after stopping treatment in the rhesus monkeys.

Typically, viral levels begin rapidly increasing after only a few weeks without treatment. The difference observed in this case points to the possibility that the early intense treatment significantly limited the number of cells harbouring the virus, and that this had an effect on the ability of the immune system to control the infection. The case also highlights the importance of early aggressive therapy when, before, children were given milder therapy to start off with.

The ability to restrict the viral load to the extent as has happened in Mississippi is unparallelled and is still an important piece in the puzzle for researchers. It is now critical to understand how this occurred and whether this period of sustained remission in the absence of therapy can be further extended in other patients.

For the Mississippi baby, however, this is not the end. The child will remain on antiretroviral treatment for the foreseeable future. But hopefully the lessons learned from this important case will help further children who are born with HIV infection to control the virus for longer, while the hunt for a cure for the virus continues.

By Kathryn Lagrue, Imperial College London

Kathryn Lagrue does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

![]()

1 Comment

Hi,

Histones are proteins found in eukaryotic cell nuclei that order the DNA into structural units called nucleosomes. It may help HIV to hide tucked away in the nucleosome. Removal of the carbonyl center of an acyl radical one nonbonded electron with which it forms a chemical bond to the remainder of the molecule could bring HIV out of hiding to be knocked out, at least says my computer.