Photograph by Eric Kilby

Last month we gave you cuddling between affectionate lions. Lest we become overwhelmed by the desire to cuddle one of these (albeit adorable) feline predators ourselves, here is a look at exactly what one of their clawed paws could do to us, including to one of our toughest components: bone. In a PLOS ONE study published earlier this month, researchers tested the ability of claws to scratch the surface of bone. The effects of claw damage are often overlooked because claws are made of a material softer than bone. Contrary to expectations, however, these researchers found that claws produced recognizable bone damage.

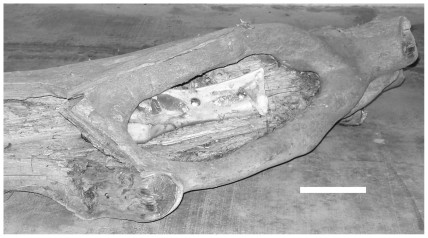

The setup was simple: let a Kansas zoo tiger participating in their enrichment program spend an afternoon leisurely playing with carefully nested cow thigh bones, also called femora. To ensure that the cow femora were only accessible to tiger claws and not to tiger teeth, researchers bolted femora down into a log that was narrowly hollowed out—preventing the big cat from sticking his snout in.

Cow femora bolted into hollow log. Image: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073811

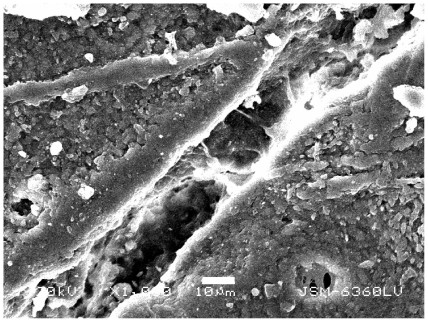

The result: impressively lacerated cow femora. Once tiger playtime was over, researchers removed the log, unbolted the femora, and microscopically examined the bone. Four scratches were clearly visible upon the bone’s surface. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image below further highlights the depths of the tiger claw handiwork.

SEM image of damage to cow’s femora by tiger claws. Image: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073811

In this particular gouge, the main diagonal chasm in the image, the gulf made by the tiger’s claw penetrated the outer covering and subadjacent bone into the bony matrix. As we can see, tiger claws can do some damage.

Damage done to bone, however, is for the most part attributed to the effects of a predator’s teeth and not its claws, the reason being that measures of scratch resistance adhere to a so-called Mohs scale of mineral hardness. The Mohs scale is graded, with talc (1) as the softest material and diamond (10) as the hardest. On the scale, harder materials damage softer materials, but not vice versa. And in our case, bones are, in fact, harder than claws. Claws are made of the protein keratin—the same stuff is in hair, wool, nails, horns, and hooves—which scores a meager 2.5 on the Mohs scale. Bone, on the other hand, scores a much more formidable 5.0.

The current research, however, shows that we can expand our understanding of scratch resistance and mineral hardness to include the effects of softer materials striking harder materials, as long as we consider the kinetic energy involved, like the action of a tiger swatting or grabbing with its paw. In essence, more could be going on in the fossil record than previously thought.

Paleontologist and PLOS ONE Section Editor Andy Farke points out in the The Integrative Paleontologist that fossils inevitably resurface as imperfect objects, which is, in part, what makes them so interesting: These fossils bear the visible marks in postpartum decay of a long and varied history. When studying bone narratives, paleontologists encounter everything from water damage to the bore marks of little critters. Including big-critter claw marks in the repertoire of possible bone modifications broadens this narrative and evidences, as the researchers themselves so aptly put it, the power of the claw.

For more information from the paleontologist perspective, check out blog posts on this article in The Integrative Paleontologist by Dr. Farke and National Geographic.

References:

- Rothschild BM, Bryant B, Hubbard C, Tuxhorn K, Kilgore GP, et al. (2013) The Power of the Claw. PLoS ONE 8(9): e73811. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073811