Punk music has never really had an easy time, but never has that statement been truer than in South Africa during apartheid. Not only were records by alternative artists not played, they were destroyed and legislated.

Up until the early 1980s there had been only one mainstream band that had dared to be multi-racial, the music group Juluka. In fact, prior to this, it had been illegal for musicians of different ethnic backgrounds to perform together in a public place under the Separate Amenities Act of 1953. This didn’t deter the punks however.

In Johannesburg, something was beginning to happen. In the 1970s, a number of promising musicians, from a variety of different backgrounds, started to form punk bands.

Bands such as National Wake, Kalahari Surfers, and Corporal Punishment were born out of this punk scene. They wrote unashamedly about issues that were facing South Africa during apartheid.

Songs like ‘International News’, by National Wake, boldly criticized the government for their use of state censorship, whilst other groups were protesting the conscription of young white males into the national service.

Ivan Kadey, guitarist for the mixed-race punk group National Wake, describes the difficulty encountered with music venues at the time:

“If the managers caught wind that it was a mixed raced band, there would often be all sorts of friction. Sometimes the gigs were just cancelled; sometimes we played despite the threats of the owners.”

These bands had a difficult time getting heard, but some venues would allow them to play. One such venue that facilitated alternative bands was Jameson’s. Jameson’s was a basement venue that opened after a few of the original punk groups had disbanded.

Warrick Sony, founder of Kalahari Surfers, states:

“Everything revolved around Jameson’s. The way that it worked was that it had a Paul Kruger license. In other words, it was a slight loophole in the law.

“There were two bars in Johannesburg that still had a Paul Kruger license, which allowed you to have black people in your establishment. Consequently, it became quite a scene.”

Other than finding a venue to play in, the punk groups also had other problems. Radio stations, including the SABC (South African Broadcasting Company) wouldn’t play their music, considering it too inflammatory. In fact, the SABC would damage tracks that the government objected to playing, to ensure they were never played.

Robin Auld, another musician who was active during apartheid, highlights this, stating:

“All art was required to be safe – any kind of presentation, so I believe it was…similar to the Soviet regime. I wouldn’t say that it stifled creativity though. For many people, apartheid gave them focus – something to push against.

“I had mates who had lines drawn through them on their records. What they would do was take a nail and scratch tracks that were deemed to be not suitable, so it was impossible for them to be played.”

At the time, word of mouth served as the main outlet for promoting music. In the absence of radio play, the musicians were constantly finding new, interesting techniques for getting noticed. This included organizing illegal gigs, as well as spray-painting their names on walls within the different cities within South Africa.

As a result of the censorship of the South African government at the time, almost all of these musicians were forgotten by following generations. However, in recent years, there has been a renewed interest in punk in Africa.

In 2012, the genre was the topic of a documentary by Keith Jones and Deon Maas, entitled Punk In Africa. This documentary focused upon the punk scene in South Africa, revisiting a history that had long been erased from common knowledge.

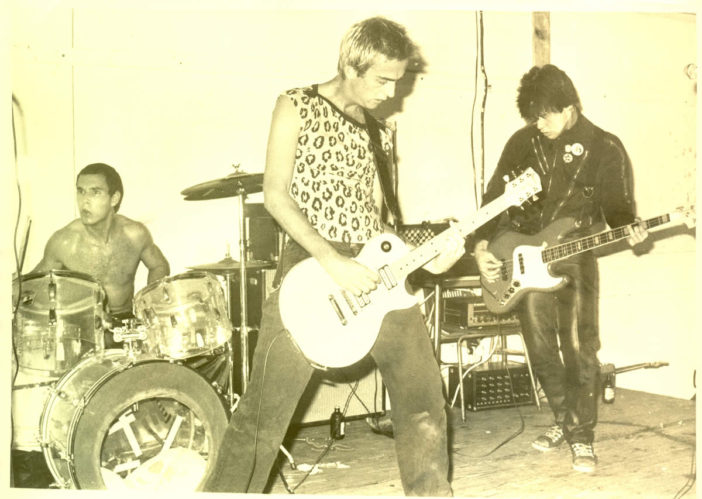

Douglas MacDonald / Martin Hendy / Michael Fleck

Michael Fleck, the lead singer of Wild Youth, the first Punk group to form in South Africa argues:

“The renewed interest in South African punk from the late seventies/early eighties is due to that film. Before that the bands were long forgotten. The younger generation did not even know we had existed.

“South Africa did not have a tradition of preserving its musical heritage and the public is only interested in what is currently big overseas. I guess this stems from the days of the cultural boycott when overseas was seen as better.”

Ivan Kadey reaffirms this statement, suggesting the documentary makers ‘provided an amazing lens through which to actually focus on this period in South African rock and popular music, by…identifying it as punk in Africa.’

As well as this documentary, many bands have also seen their albums rereleased without further opposition. These include Wild Youth, National Wake and Warrick Sony’s Kalahari Surfers.

When asked what he believes caused this renewed interest, Warrick Sony says:

“The past informs the future. I think we are looking now at a point where people are wondering where the protest music is. If the kids of the sixties had to look at today, they’d wonder why there is so little put out there.

“There is a lot of stuff in the hip-hop realm – protest stuff – particularly in South Africa. I think there is complacency in places such as America, where I think people do stuff for money a lot. I don’t think the two can go together.”

Whilst the apartheid government may have tried time and time again to quell punk in Africa, it remains evident today that they have failed. With global interest in South African punk rising, these musicians have secured their place in the nation’s complex cultural history.